Session 1 continued - Game Development Introductions

So if you’re new to game development, welcome to a whole new world of fun where the only limit is your imagination (skills can be learned, creativity must be something from within). If you have been around with programming or basic game development, most of what will be covered in this tutorial you should already know, feel free to comment and improve where necessary.

The original digipen webcast for this session can be found here on the codeplex site for this tutorial

Over the course of this tutorial, I’ll be going over:

- Introduction: covers the basics of what you’ll need to know

- C# overview: a programmers intro guide to C# (good if you’re starting out, skip if you are already a C# vet)

- Game components: covers the necessary plumbing to get your game on

- Building the demo: building the blocks and components of your game

The Second section of the first tutorial starts here; it is basically used to explain what a real-time interactive concurrent events application are and reveal some of the trickery used in games.

If you haven’t already, download the demo and have a play, this will give you a feel of what we are aiming for at the end of this tutorial (bear in mind it’s not the finish as we aim to go that bit further than the original Digipen tutorial went)

- Please note that the game is implemented with simplicity in mind in order to show clearly the game architecture and components

- Try to spot the events of the game happen concurrently

- Look for the objects are moved at real time using the keyboard interaction (arrow keys and space bar)

What you saw was a real-time interactive concurrent events application simulating a starship fighting enemies in space.

Why concurrent?

The starship, bullets, enemies, sound effect, music, and text exist and move at the same time as a series of coincident events

The list of coincident events:

- Testing the keyboard for up, down, left, and right key strokes

- Scrolling the background

- New ship position calculation

- Testing if the fire key is hit

- Creating a bullet

- Calculating the new bullet position

- Testing for collision between each bullet with each enemy

- Calculating the new enemy position

- Playing a sound effect when an enemy intersects with a bullet

- Playing the explosion animation when an enemy intersects with a bullet

- Updating the texts

- Playing the music

- Etc.

Why interactive?

Interactivity enables the player to involve themselves in the game or enable a computer controlled character through the use of controls, these could be:

- The player decides when and where to move the ship

- The player decides when and where to fire a bullet

- The game AI decides when to attack

- The number of bullets increases each time a bullet is fired

- The score updates each time an enemy is hit

- The enemy explodes when hit by a bullet

- Etc.

Why real-time?

No matter what game you are playing, the event you see are always happening in real-time, even when the games is paused and no obvious activity is happening, such as:

- When the ship moves, its new position is calculated at run time

- The collision between the bullet and the enemy is detected at run time

- The enemy’s new position happens at run time

- The text updates at run time

- Etc.

How do we write an application with concurrent events?

In order to have a computer program to run concurrently, we have to take the following into consideration

We need to be able to execute several instructions at the same time, it would be nice if we have a CPU dedicated for each event but usually, we only have one CPU (although some more modern processors have more than one core (dual/quad) and consoles such as the Xbox360 have 3 cores)

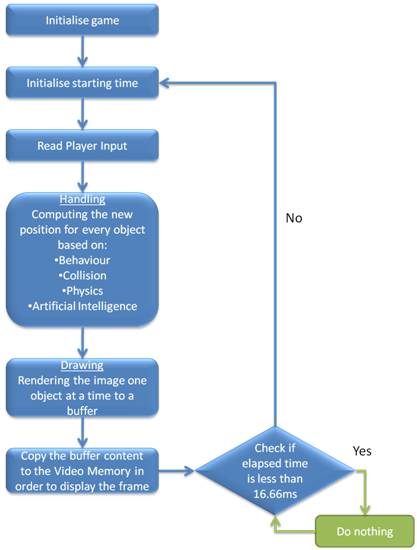

We also need to execute in parallel several instructions. If we divide the second into 60 pieces, each piece would be 1/60 or 0.016 a second (this is also 16.66 milliseconds), If during each 16.66 ms we update sequentially all game components then the game components would be updated 60 times a second. The player will then get the illusion that the events are coincident or parallel – this means that the events are happening at the same time.

In reality the events are not parallel; they are pseudo-parallel. The events do not happen at the same time, they happen sequentially because the events are updated at a fixed interval of 60 times a second, the illusion of concurrent events is achieved.

Each 16.66 ms duration is one game iteration, since the iteration repeats as long as the game is playing, the concurrent events are controlled by repeating the game iteration through a game loop, the game loop also makes the series of events update as a motion picture or pictures in motion.

Game loop

The game loop iteration duration greatly affects the illusion of concurrent events, If the duration of the game iteration is long, let’s say 0.1 s, then the simulation will feel slow. Why?, Because the reaction to the events happens only 10 times in one second. This is commonly referred to as Frames per Second (FPS).

On the other hand if the duration of the game iteration is short, like 0.016 s, then the Simulation feel smooth, Why?, Because the reaction to the events happens 60 times in one second. Consequently, the duration of the game iteration is called the frame, therefore, the game speed is measured by frames per second

For example, when we say a game speed is 60 frames per second or 60 f/s or 60 fps, then the game iteration duration is 16.66 ms.

The ideal FPS we usually aim for is 60fps to give a feel that the game is moving as we would.

Below is an example of the Game Loop in action.

How do we add interaction at real time with concurrent events?

During the game iteration, we:

- Detect and register the user input

-

Execute the behaviour of each object; usually the object behaviour depends on:

- Input from the keyboard

- Input from other objects

- Collision status

- AI

- Etc.

- Once all the objects are updated, their position and status at the current game loop is determined we render the objects

What we just mentioned means that the objects are rendered as many times a second as the game speed, for example in a 60 fps game, the objects are rendered 60 times a second.

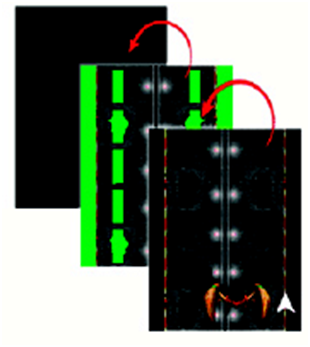

During the beginning of the rendering during the game loop, a blank frame is prepared, and then all the objects are rendered sequentially. When an object o moves, its position at game loop n is slightly different than its previous position at game loop n-1; also, its position at game loop n+1 would be different than the position at game loop n

Below is an example of the moving bullet at a low frame rate

| Frame n |

| Frame n+1 |

| Frame n+2 |

Being drawn several times consecutively, the sequence of different pictures and different positions provide the illusion of a motion picture, as a matter of fact, movies at the movie theatre play at 25 pictures per second

Game components

To finish off, here is a list of the components that we will cover during the tutorial:

- A Background: static object

- Sprites: dynamic objects

- Text

-

Sound

- Sound effects

- Music

- Object behaviour: specifies its interaction.

There are other components we can add but let’s start with the basics. It is also worth noting that 3D games use the same components plus a few which are specific to 3D.

End of part 1

That’s the end of part one of this tutorial series. The next section covers the C# programming language, useful if you’re new to programming or are coming from another language.

Most of the information comes direct from the C# programmers reference with a few additions (mostly by Digipen) to aid newcomers.

If you are already proficient in C# you can skip this section, however I’ve always said it’s always worth going over old ground for those things you may have forgotten or are new.

Catch you on the flip side.