How to become a better GIT Collaborator

GIT appears to have become the defacto new source control system for the masses, in fact most if not all open source projects of late are managed through one GIT repository or another due to its alignment with SCRUM style development and team collaboration capabilities.

On the other side of the coin, it is certainly one of the more complicated management systems I have seen for some time now, GIT basically has its ways and if you do not fall in line you will become trapped, GIT is not perfect but as DVCS systems go it has a lot to offer.

The main reason for this article is to show you some of the best working practices for working with open source projects, most tutorials out there show you how to use git itself and sadly most of those are all about the command-line functions, however I like others like my GUI infested world. So instead of teaching you git, I will walk you through how to be a better GIT contributor.

Prerequisites

There are many GIT clients, some better than others and each have their strengths, I actually use 3 clients predominately for different tasks. I could happily get away with just one and work effectively but I like the flexibility that each of the clients I use have.

For starters, you will need GIT for Windows which was born from the hugely popular MSysGit.

There are other clients for other platforms and where the following instructions may work for those platforms, the primary focus for this tutorial is for Windows clients

Without the above you will be struggling as other clients build on top of the MSysGit foundation (some include a version of it with it but work better with the latest client installed)

Git for windows will give you many explorer and command-line features (plus one or two useful GUI scenarios) and is a good start. If you are comfortable just using command-line then arguably this is all you need, such features include:

Git interpreter – command-line

Git Explorer extensions for repository management

Git GUI Browser

All are good but to be honest very limited.

To get us further there are several other clients to consider:

TortoiseGit – IMHO the best explorer management client around

GitHub for Windows – crafty Metro like dashboard for managing local repositories

Visual Studio Tools for Git – Git tools for VS from the TFS team

SmartGIT – a paid for Git client with a lot of features

SourceTree – A multi-functional Mercurial and Git client

Git-cola – a python based git client

GitEye – Collaboration focused git client with task management features

You can find more clients listed for other platforms here.

Personally I use TortoiseGit for working in explorer and syncing with remote repositories, GitHub for windows to manage my repositories and VS Tools for GIT when working in VS.

GIT hosts

Almost all source repositories offer GIT nowadays, such as:

GitHub – the first and main site of choice

BitBucket – wildly used although some work needed to get clients to play nicely with it

Codelex – recently added support but not as full featured

Team Foundation Service for GIT – Visual Studio’s TFS system added GIT support in 2013, worth checking out – it’s free.

Assembla – great site but you need to pay to get the full features

Beanstalk – a paid for, high availability system with high end syncing capabilities

Indefero – Open source system based on google code but with more client support.

ProjectLocker – Full-fledged project management system with SVN and GIT support

Each host has its benefits and drawbacks, so personally I use the first three as they let me work effectively but you should choose what fits your usage pattern

You only need a host if you are going to host your own project, if you are collaborating with another project then the choice is obviously made for you as you cannot mix n match hosts, well you can but it becomes a management nightmare ![]()

Best Practices

in most of the projects I have worked on or with, there have been a few standard “rules of the road” to live by:

You should:

Work in as small chunks as possible

Only work in your private fork or repo

Test your work against the latest main / master branch before submitting fixes

Talk about your fixes on the forums and comment on other devs suggested changes to keep you up to date

You should never even consider:

Submitting a change more than a month old (depending on the velocity of the host project)

Repeatedly updating your dev branch with your fixes in, as they will be lost in the mire

Doing a clean of your local dev branch to switch to another without checking all your changes have been committed

Telling one of the main project contributors / hosts they are wrong, it just does not end well

Do this and you will be shot!:

Attempt to submit a PR from the main dev branch instead of your own fix branch

Copy code from a decompiled DLL or CodeProject post in to a repo without published permission. Copyright is real!

Publicly slam a project host for not listening to you, it is their project after all.

All in all just try to be a nice puppy

Getting Started Contributing

Right, so you found an open source project and you feel you have something to add or something you can help out to fix, now what, just what is it you need to do to get started. The answer is fairly straightforward and simple when you follow these steps.

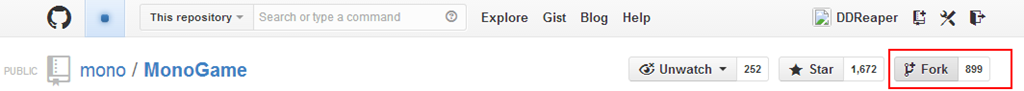

1: Fork

Depending on which site the project is listed on there should be an option to “Fork” the project, this will create a mirror image of the project just for you on the site. Do not worry about it taking up space because only your changes are logged against you. GIT servers are usually clever enough to not create duplicates of files everywhere. Fork hard and Fork often.

Main Repository:

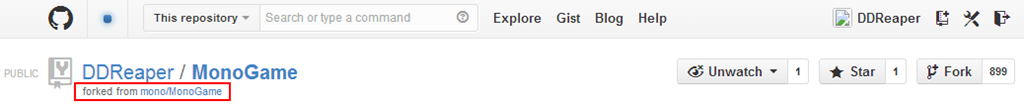

Forked Repository

And yes,, you may have noticed you can Fork a Forked repository, there is no end to the madness ![]() (but I would not if I were you, unless you are merging)

(but I would not if I were you, unless you are merging)

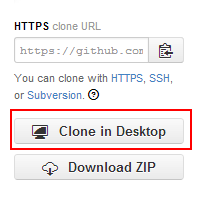

2: Clone

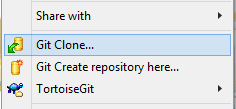

With your own Forked repository in hand, it is now time to get a copy of that locally, basically copying the source to your machine whilst keeping a link to the site.

There are a number of ways to do this, the simplest is to click on the “Clone in Desktop” button on the site (if it has one) which will launch up your local Git Client, set up a local repository and start copying it down to your machine:

If you do not have a compatible client installed, you may get forwarded to install one or it simply won’t work.

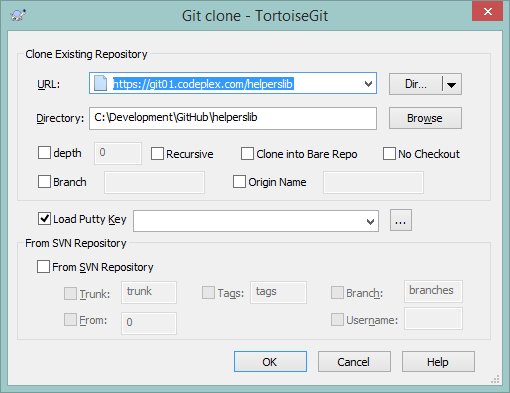

The other method is to copy the Clone URL (link to your online repository) and then manually use your Git client to Clone the repository onto your machine:

|

|

| Tortoise GIT right click menu | TortoiseGit clone prompt, source and local directory |

If you choose to simply download the project manually and unzip it, that can work but you will need to add a source (shown later) to the local repository once you create it.

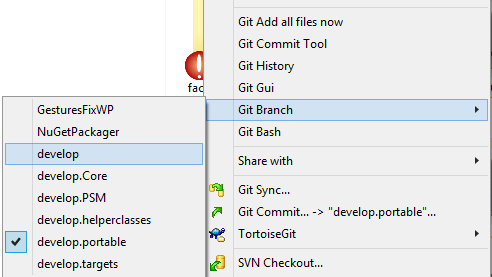

3: Branch

With the Forked project hosted locally, you now have a copy of the Main / Default / Master branch of the source project, first and foremost you should keep this as clean as possible and whenever you can, keep it in sync with the original project.

NEVER, NEVER, NEVER to infinity, commit changes to the Main / Default / Master branch.

When you are working on fixes or improvements, you should always do it in a local branch from your forked repository specific to the fix at hand. Doing 3 fixes, have 3 separate branches for each fix (unless they are directly related or dependant).

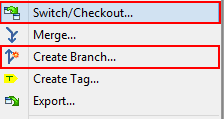

To create a branch you have three options:

Do a Switch / Checkout whilst selecting the “new branch” option – effectively selecting another branch to work on but creating a new one instead.

If your client supports it, select “create new branch” – almost the same as the first option but not…

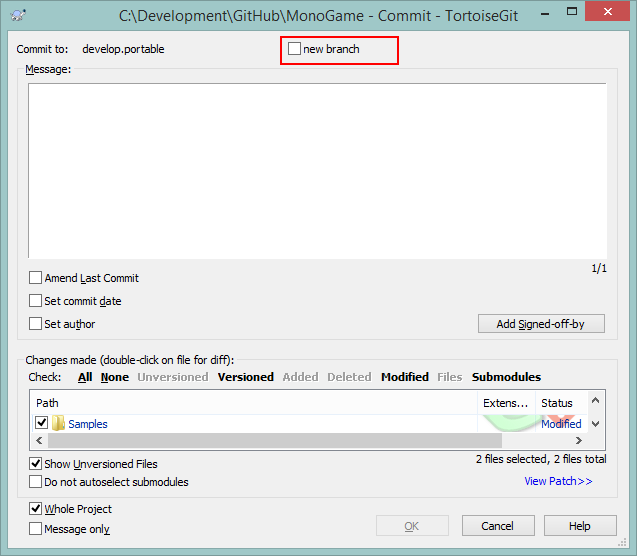

Start making changes in the main / default / master branch but when you “Commit” your changes, elect the new branch option – this will move your changes to a brand new branch.

|

|

| TortiseGit Switch/Checkout & Create Branch | TortoieGit “Create Branch” option on commit |

The safest thing to do is obviously option 1 or 2 as this protects you in-case you need to update the main / master / default branch while you are working (a hopefully unlikely situation). It also protects you from forgetting to select the “new branch” option on commit and accidentally merging your changes with your local main / master / default branch #facepalm, If this happens then you are really stuck (you can go back but then you will lose your changes and ultimately you have dirtied your local copy of the main / master / default branch)

Your local repo is now ready for work.

4: Do Stuff

You’re off, your rock’in and you are doing your code things.

Try to remember though to keep fixes small, if it is going to take a while then you have some choices:

Use your current branch as a dev / poc branch only. Keep a track of your files and then move them to a new branch based on the current master before submitting (more on that later)

Keep working remembering you are likely going to have to update the project from source just before you submit

Decide what you were doing is just not worth it and move on

There are many ways to work when you are contributing, the first option is fairly well understood having your own private dev branch which you keep up to date with source and then take your specific fixes into a new branch based on the clean master / main / default branch when submitting the Pull request.

Ideally you want to be quick, focused and just touch what you need to in order to complete what you have been working on, No One likes mass changes all mixed up in one change.

Remember:

Keep it small

Keep it focused

Change only what you need to

And everyone will be a lot happier. It is better to have 10 small separate branches than one big monster change, it is harder for the project team to test and make a decision on whether they want your hard work.

Now just “commit” your changes to your local repository when you are happy. you can do this as often as you like and gives you the option to go back if needed. If you are still on the master / main / default branch then be sure to check the “New Branch” option or you will end up running and screaming round the office later like a mad person. #BeenThereDoneThat

5: Push and Pull

So you got your changes done and you have tested it and are happy, now what?

First off you need to update your local dev copy of your code with your hosted forked repository, this is called a Push request. You can do this as often as you like and it wo not affect anyone else, in most cases you will do this after every commit just to ensure you changes are backed up remotely. Note you cannot push if you have not committed (no half way)

As with everything there are several ways to start a pull request, some clients offer this option after performing a push request, however I find the best way is to go to the site hosting the forked repository and using their button or command. GitHub now actually highlights on your forked repository page (for example) a button to start the process.

Once you kick this off you will be asked what to call your Pull request, by default most sites copy the test from the last commit but you should be able to change it. Make the title meaningful and put as much information in the description as possible to accurately describe you change / addition.

Then it is up to the original projects admin / organisers to check out / test and decide whether to merge your changes into their main branch. Once merged you can delete your dev branch as the code is now located in the main / default / master branch.

Keeping up to date

Now in the course of your work you obviously want to keep your local repositories up to date with the main projects source, this is relatively a simple task but opens up one area of confusion for most newcomers.

In order to update your local dev environment with the main projects source you need to do a Pull request (hold on did not I just do that the other way around?).

A pull request simply means you want to take changes from one project and add them to an external one, synchronising the two, when you did a pull request from your forked repository what you were actually doing is asking the main project to copy your new branch to their repository so that they can do a merge with that remote branch. Here we are doing the same but the other way around, you are going to pull the code from the main project and add it to yours, the only difference is that instead of a new branch, you are updating your local copy of their code. Make sense?, a pull copies code between projects.

Now, so as not to pollute any development work you are doing, make sure you have checked in whatever changes you were doing and then switch / checkout the main / default / master branch in your local repository, either using the same technique as mentioned before but not choosing the “new branch” option and selecting the main / default / master branch, or using the handy explorer context menu that MSysGut (Git for Windows) gives you:

Once you have done that CHECK AGAIN!!

I wo not tell you just how many times I have just changed / switched branches, started working only to realise it actually DIDN’T do it.

Be sure, be safe and check again, it is rare but git clients wo not let you change branches unless everything is tickety boo with your current branch, it may be as simple as some dirty files or that you have not committed. In most cases git clients WON’T tell you there was a problem (damn annoying)

With experience you will find a client that works well for you, usually if there is a problem I use a full GUI route or revert to using the command prompt and eventually it will tell you why it cannot switch branches.

Just find the problem, clean it up and when it finally registers back on the main / default / master branch you can move on.

Setting up an upstream source

To successfully update your local source from the main project, you simply need to tell it where the source is. As it is not your main repository on your forked repository your local client has no knowledge of it (personally I would like GIT clients to recognise it is a forked repo and do this for you but until then..)

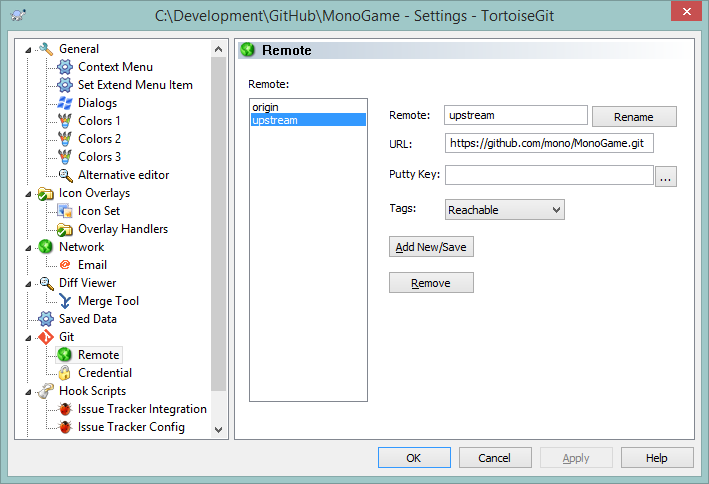

Again the process is very simple once you get used to it. Now depending on your client you need to locate your “Remotes” configuration for your local project, this could be either:

A remotes setting in your GIT project properties (as shown below for tortoiseGIT)

A Manage button next to your source selection (usually in the push / sync window)

A sources or manage button on the switch / check out option

|

Remotes windows in TortoiseGIT project settings

Once you find it you should find you have just one “Remote” in the list, this is the link to your forked repository. We simple need to add another one for the Main Projects Git repository. If you have set up your local repository manually, you can also use these instructions to setup a source to your own forked repository as well.

The convention is to call this new “Remote” the “upstream” source, as shown in the example above you just add a new item, name it upstream and then paste in the Git HTTP path to the main project source. If you do not have it to hand, just browse to the main project on it is GIT site and copy the GIT clone url.

you should note you can add many remotes to your project, I am sure this was done for flexibility but cannot for the life of me think why, maybe so you can access multiple forks from the same code branch and be able to access them, I have never done this so I wo not elaborate further.

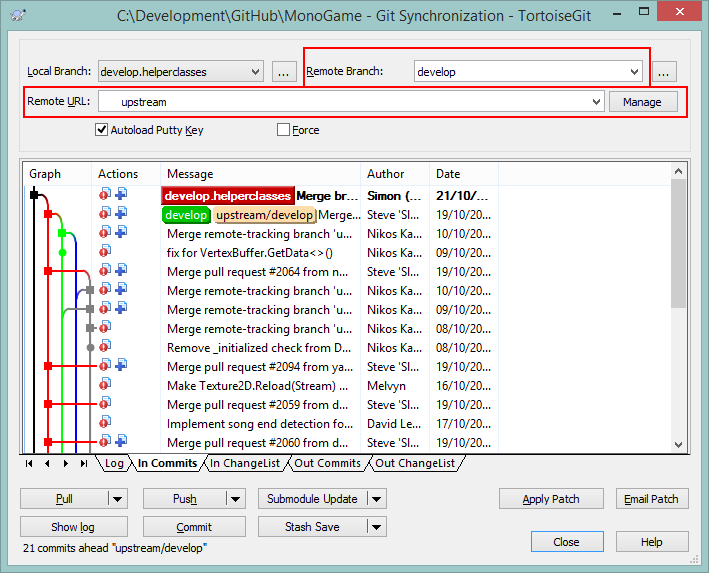

Now with your new remote added, use your GIT client to do a pull request but this time change the “Source” to our new “upstream” path:

BEFORE you actually throw the switch, be sure to check:

You have the correct REMOTE branch selected you want to pull from, do not assume its always going to be the main / default / master branch

You have selected the correct “Remote” URL / source

Once you have “Pulled” you should get a report on what has changed since you last updated your source from the main project, including all commit messages and information about which files have changed. If you wish after you have pulled, do not forget to push merges back to your forked repository to keep it up to date, just remember to change the source back to “origin” or you will be scratching your head as to why it wo not upload ![]()

You do not have to just do this from your local main / master / default branch, you can do this from any local branch you have. So if you are using a local dev branch which you want to keep up to date, or the main project admin asks you to test (just at the end) against the latest source because too much time has passed before they will accept and merge it.

Try to keep in mind though:

Keep your local master / main / default branch clean from your work, it should mirror the source project

Do not submit requests with branches that have been refreshed from source unless asked to by the main project admin

You can pull code from several branches in to one big local one, just do not expect a PR to be accepted from it though.

Be a good collaborator and keep your main project admin happy. Do not forget one day it could be you.

Signing off

Well I hope you found this little article useful, as usual if you have any comments or questions just post them below and I always try to answer every single one, even if you want to say it is a load of rubbish and that is not how you do it, I welcome different perspectives. This is just how I have been taught to do it from many a disgruntled admin who complained about my contributions (and No I am not naming names, i learned a lot from every negative)

I may follow up with a little article on being a project admin and accepting PR (pull requests) and how to test and merge them yourself if you are running a project, will just have to see.

Laters.